An American Masterpiece

VIE Magazine

By Tori Phelps

September 8th, 2014

““Oh yeah, I went to Harvard for grad school.”

Only with a résumé like Barbara Ernst Prey’s does Harvard become an afterthought. Then again, this is the artist who is regularly named among the most important painters of our time. An artist who, at age seventeen, counted then-Governor of New York Hugh Carey as one of her first buyers.

So maybe Harvard has some competition when it comes to life-defining moments.

One of the best-known modern American watercolorists, Prey is mentioned alongside legendary watercolorists like Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent. Ironically, the medium with which she’s so closely associated was initially attractive to her simply because it was not what her mother, a talented oil painter, favored. While trying to avoid comparisons, Prey ultimately discovered she loved the fluidity of watercolor and the intensity of color she could achieve. It also suited her personality. “You can’t be rigid to paint watercolor,” she says. “Things happen, and you have to be very flexible to get to the finished painting. It’s a journey.”

Her mother can also be credited with Prey’s enduring interest in landscapes. From childhood, she would tag along on her naturalist mom’s alfresco painting excursions, and even today she prefers to paint outside as much as possible. “The landscape is an incredible inspiration for me—the architecture of the country, as well as the stories of its people and places,” she says.

Clearly, Prey’s upbringing provided an ideal springboard for artistic success. Not only a painter but also head of the design department at renowned art mecca Pratt Institute, her mother incorporated art into every nuance of family life. New York City museums were her daughter’s playgrounds, art books her entertainment, paintings her wallpaper, and still-life sessions within their in-home art studio her typical Saturday morning. “At the time, I thought that was everyone’s experience,” she says wryly.

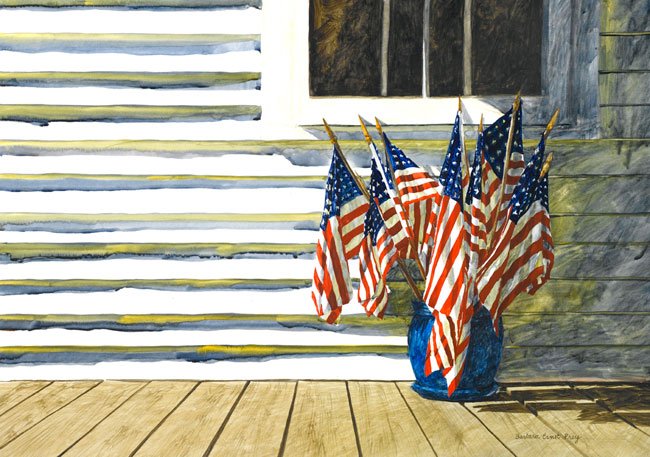

The Collection (Watercolor 22” x 30”)

Prey won a scholarship to the San Francisco Art Institute in the tenth grade, sold an oil painting to the governor of New York a year later, and then settled in at Williams College to learn from the architects of the Williams Mafia. Led by the “holy trinity” of Whitney S. Stoddard, William H. Pierson Jr., and S. Lane Faison Jr.—one of the real-life Monuments Men portrayed in the 2014 movie—the Williams art history department churned out staggering numbers of successful artists and major museum heads, a phenomenon that came to be known as the Williams Mafia.

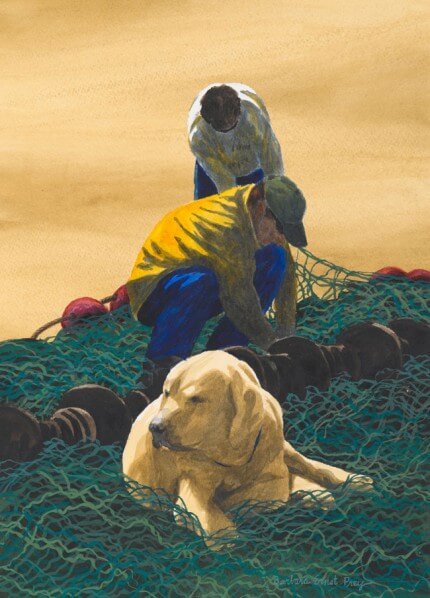

Wayfarers (Watercolor and drybrush; 22” x 30”)

Barbara Ernst Prey soon joined their ranks, landing an internship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art before earning a prestigious Fulbright Scholarship to continue her painting and studies in Germany. While there, she took a job as personal assistant to a German prince, an experience she calls “wonderful” in and of itself, but one which also introduced Prey’s work to influential members of the glitterati, who began snapping it up. “I had a number of shows there, and a lot of the European nobility collected my paintings,” she recalls.

Her bottom line wasn’t the only thing in bloom during that time. Prey traveled throughout the Continent, visiting many of its illustrious museums and internalizing the images in a way that would later influence her art.

Back in the U.S., she worked in the modern painting department at Sotheby’s and started doing illustration work for The New Yorker, which led to more illustration gigs for publications like the New York Times and Good Housekeeping. Then came another international opportunity, this time from the Henry Luce Foundation, which sent her to Taiwan for a year. She lectured at universities, studied with a master Chinese painter, sought out museums all over Asia, and brought home a new facet to her artistic repertoire: large-scale paintings.

Oh yeah, and a master’s degree from Harvard was in there somewhere.

With a remarkable national and international education under her belt at a still-tender age, Prey settled outside of New York, where, simply by indulging her love of painting, she has cemented her status as one of the most highly regarded artists of her generation. Amazingly, nothing about her career has been calculated—even its origin. “I didn’t really think about it,” she admits. “People started to collect my work, and I didn’t look back.”

Starfish and Geraniums (Watercolor and drybrush; 30” x 22”)

With the benefit of time, she appreciates the rare convergence of events that helped launch her career—starting with the fact that her early supporters had names like Luce, Mellon, and Rockefeller. Now, it’s easier to name illustrious people and venues that don’t possess one of her paintings. Prey’s works are in presidential libraries; among the collections of senators, congressmen, ambassadors, and museums like the Smithsonian; and in celebrities’ homes. She’s particularly tickled that Tom Hanks has one of her pieces in his bedroom. “That’s pretty cool,” she says.

Cool? Yes. Surprising? No. After all, her entire career has consisted of a series of jaw-dropping highlights. Among the most recent was her 2008 appointment by the President of the United States to the National Council on the Arts, the advisory board of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). She’s the only visual artist of the fourteen-member board, and the fact that she was nominated from New York—home to a staggering number of talented artists—speaks volumes.

The six-year term entails advising the NEA on grants for arts programs in the U.S. Reading every word of stacks and stacks of grants may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but Prey is thrilled to put in the time. “There are so many gifted, extraordinary people out there that we support,” she explains. “I’m so impressed with the breadth and depth of the arts in this country, whether it’s basket weaving in Maine or fiddling in Kentucky. I’m overwhelmed by the creativity.”

Her appointment to the National Council on the Arts wasn’t her first brush with a presidential assignment. Prey was the artist behind the White House Christmas card in 2003, a rare honor that led to an even bigger honor: the inclusion of her art in the White House permanent collection. “The only way to be part of that—without dying first—is to do a Christmas card,” she reveals.

She’s also made her mark on the international political scene as part of the U.S. Department of State’s Art in Embassies Program. Her work has been exhibited in embassies in Paris, Madrid, Oslo, Prague, Seoul, Mexico City, and many more. At last count, more than a hundred of Prey’s prints have held places of honor in U.S. consulates and embassies.

Meeting House (Watercolor; 21” x 29”)

She takes her role as an ambassador for American art seriously. Even when she’s partnering with a quintessential American institution like NASA, her intention is that the images resonate with viewers from all backgrounds. They must. She’s received an impressive four commissions from NASA, including a painting of the International Space Station and the emotionally fraught tribute painting of the space shuttle Columbia. Prey was given complete freedom with the Columbia design, and she settled on a depiction of the ill-fated shuttle during takeoff. “I consider it to be a very optimistic moment,” she explains of the decision. “It was the moment when all of the astronauts were realizing their dreams.”

The image belongs to the nation, but more important, according to Prey, it belongs to the families left behind. In a ceremony at Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the astronauts’ families received a print of the tribute painting, and many conveyed their appreciation to Prey.

Not surprisingly, her work was included in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum exhibition NASA/Art: 50 Years of Exploration. Still seemingly in disbelief about her inclusion, she says, “It was Normal Rockwell, Andy Warhol—and me.”

Prey may still struggle with the notion that she’s one of the brightest stars of the art world, but the art world has no such reservations. Her works now hang beside artists she studied in school, and she’s included on lists with Eleanor Roosevelt and Harriet Tubman, fellow recipients of the New York State Senate Women of Distinction Award.

Columbia Tribute, NASA Commission, Collection NASA, Kennedy Space Center (Watercolor; 30” x 22”)

Meeting House II (Watercolor; 18” x 28”)

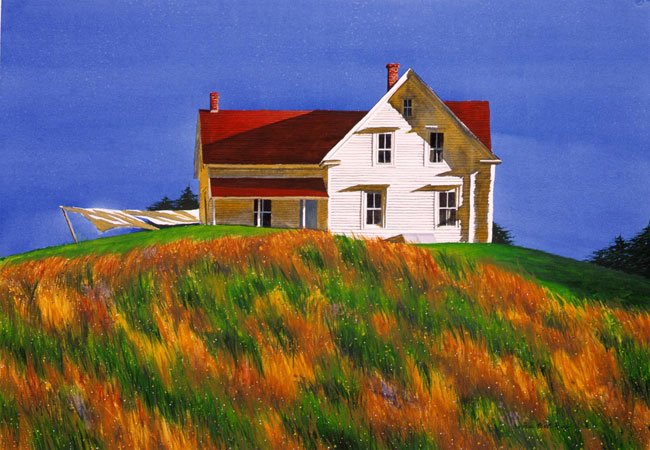

The Simple Life (Watercolor; 28” x 39”)

She hasn’t forgotten where she came from, however. She maintains strong ties with Williams College, helping to inspire new members of the Williams Mafia and serving as an adjunct instructor at the school, where her daughter recently graduated as well. She also opened an eponymous gallery in Williamstown. The gallery is one of the only places where the public can view and, perhaps, buy a Prey original. “My work is hard to come by,” she says. “I don’t do many shows, and there aren’t a lot of my paintings out there to purchase, so the gallery provides a good opportunity for people who are interested.”

It also serves as a training ground for aspirants to the art world, thanks to her commitment to employing student interns. Inspired by her parents, both of whom were professors, she’s passionate about using her gallery as a learning environment for the next generation, from college interns to the underserved children she welcomes for tours.

God and Country (Watercolor; 28” x 21”)

In addition to teaching and mentoring, Prey gives back through her support of environmental causes, which includes raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for organizations that support land trusts and open spaces. As she points out, “I’m a landscape painter, so open spaces are pretty important.”

Lobbying for conservation helps preserve the things that inspire her, but she doesn’t presume that the feelings she’s moved to convey on canvas come across the same way to others. “My experience has been that everyone views paintings through their own lens,” she says.

She’s constantly surprised by those lenses. A good example was the series of paintings Prey completed after 9/11. On a visit to Maine, she created one with a “God and Country” theme—a church and a flag—that the ambassador to France chose for the entry to the French embassy. Why? Because the ambassador saw the colors of both the French and American flags, which represented a spirit of camaraderie fitting for the venue. “You just never know what people are going to take away,” she comments.

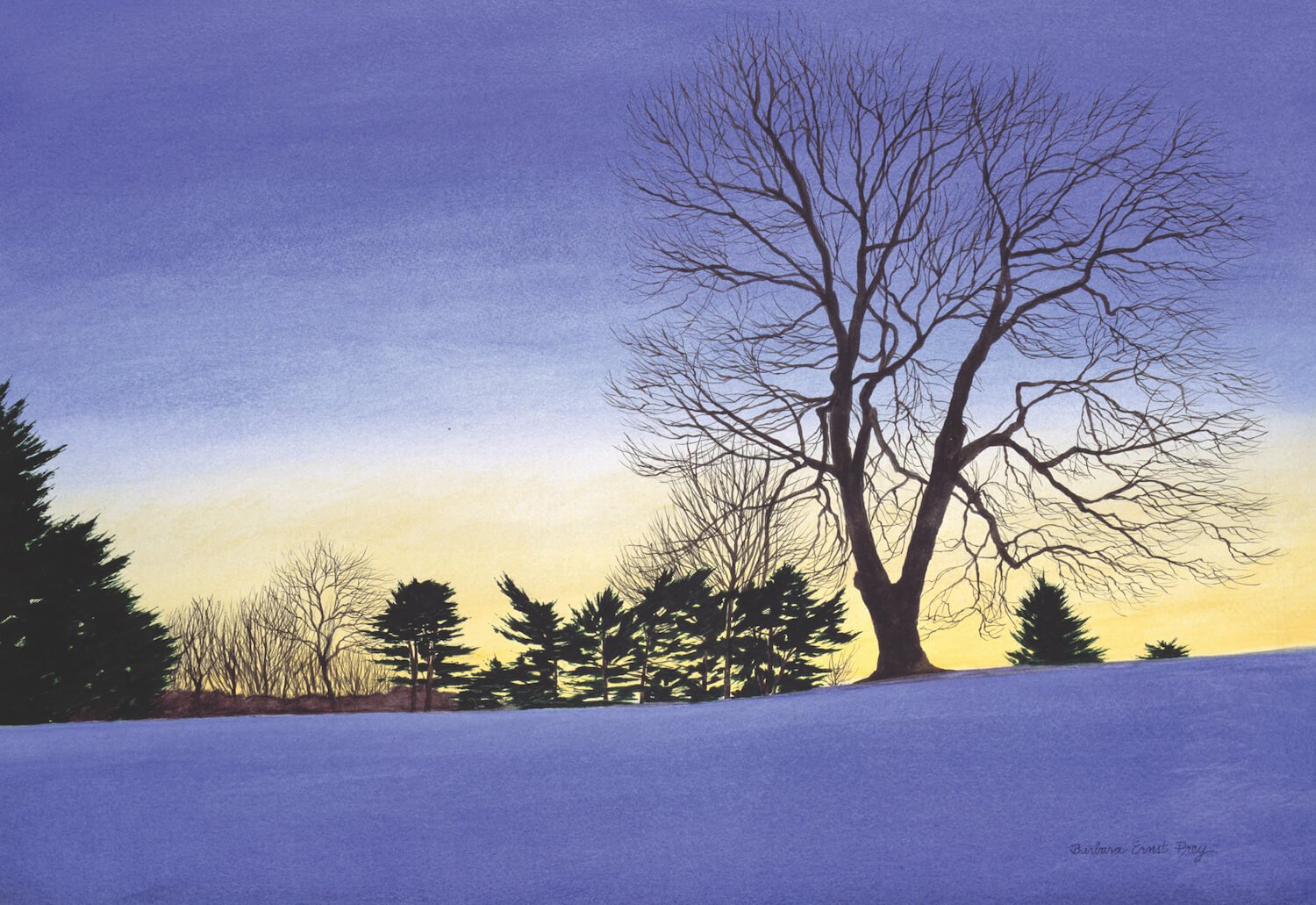

Twilight (Watercolor; 22” x 30”)

Prey has no desire to force her own perspective. Rather, her wish is that audiences simply connect with a painting, let it inspire them, educate them, and perhaps motivate them to do something. Mostly, she wants to communicate that we’re all part of a bigger picture.

And given her background, she’s in a unique position to do just that. Her international studies gave her techniques like Chinese brush painting and an eye that was informed by visits to nearly every European museum. Still, her work is distinctly American. More precisely, it’s distinctly American from a female perspective. “The fact that I’m a female landscape painter is unusual. When you think of artists in that category, it’s Hopper and Homer,” she says. “But I’m creating a contemporary voice as a woman living in 2014.”

Her trailblazing has resulted in a portfolio so impressive that she was honored with her own Paris retrospective several years ago. It was a homecoming of sorts, as a number of her first exhibitions as a young artist took place in Europe. The retrospective was a huge hit with the public, earning raves from the Wall Street Journal as their arts pick in Paris and drawing more than a hundred people daily, even during a transit strike. It was also satisfying personally, both because her work reached an audience largely unfamiliar with modern American watercolor and because she was able to see paintings she hadn’t laid eyes on in decades. On loan from embassies scattered across the globe, from prestigious museums, and from collections of the rich and famous, these Prey works were on display in a single space for the first time. “They were brought back together,” she says with palpable pleasure. “It was very exciting.”

For many, a retrospective represents the twilight of a career, but Prey may just be warming up. Lately she’s been pushing herself in different directions—her watercolors have become larger, her colors stronger, her subjects more diverse—and she’s returning to oil paint, a medium she hasn’t worked with seriously since she was seventeen. Over the past year she’s painted a new collection of oil paintings, which the public will get to experience at her Williamstown gallery. She’s also prepping for a show in Maine this summer and doing a portrait of James Watson, one of the scientists who discovered DNA.

If she frets about anything these days it’s the fact that she has too many ideas and not enough time to pull them off. It’s the exhilarating, exhausting life of an artist. “I’ve had incredible opportunities,” she concedes, “but being an artist is both a blessing and a curse. The curse is that I’m always looking, always filtering my perceptions. So I’ll never retire.”

On behalf of all art lovers: we’re okay with that.